Why do we fall for sovereignism | Vlad Nancă on representing Romania at the Venice Biennale of architecture & more

The week has been a whirlwind of emotions following the results of the presidential elections' 1st round and we still have another 10 days until we find out the direction of our country.

On Sunday night I fell asleep refreshing the AEP election results page. I woke up at 4am for one last refresh and saw Nicușor Dan was in the second round. I was too sleepy to express my joy. The next morning, when I woke up with the same good news, I still failed to express my feelings in any way. The percentage with which his opponent entered the second round blocked me for having any possible expansive reaction.

Several days passed since then. Days in which I've been refreshing the news pages countless times, listening to loved ones express their fears, reading countless articles and social media posts about potential scenarios to come, and I still can't express myself in any way. This is, in fact, the first time I’m trying to give voice to my thoughts. It all seems far too unpredictable for me to be able to intuit who has a better chance, or what will happen after May 18th. I think that G.S. exhausted a large part of his electorate in the first round, while no one gave N.D’s a chance to get this far anyway. Not only when it comes to the presidential elections, but also as an independent candidate running several times for Mayor of Bucharest. And here he is. I don't think this is the time to be pessimistic or superior, to consider ourselves defeated or to get into conflicts with those around us. But rather to listen, to stubbornly explain our point of view, to be patient with those who don't vote like us.

I understand the people who voted for George Simion – Teodora Munteanu manages to explain so lucidly in the article below how we ended up in the situation we are in, moving so quickly towards extremism. I also understand the bewilderment of those like me who voted for Nicușor Dan. What I don't think many people on both sides understand is that we ALL voted against the current system, which no longer has any credibility after more than 35 years of stealing, lying and not giving a damn about us. We all voted for change, with good faith and hope. However, not all of us (9 million voters) understand or know the history, and too little of us have some understanding of how economy works and what are really the stakes.

In order to shed a bit of light over everything, I have invited two very smart and well-informed young ladies to write for this edition of EFMR’s newsletter, in the hope that we will be able to better communicate with those we cross paths with over the next 10 days. Journalist Teodora Munteanu writes the lead article, in which she explains how emphasizing the differences between us and them has united the extremists and where the hatred for politicians comes from, while Ruxandra Gîdei (4fără15) recommends 3 books we should read to better understand the rise of extremism and populism around the world.

To take our minds off politics and ease our anxiety, we also have talks with two well-known and very prolific artists. Vlad Nancă, currently at the Venice Architecture Biennale, where he is representing Romania with Muromuro, and Dumitru Gorzo, the visual artist who needs no introduction and whose exhibition is still open at Ars Monitor. We end with some recommendations from Morocco, the country I visited a month ago and which redefined my perception of Muslims.

In the hope that we will meet again full of hope for the June edition of the newsletter, I leave you with a little bit of politics, some good reading recos, a view into the art world and a little bit of traveling, in the hopes that you will find something useful in these extremely tense days, for your mind or heart.

Laura x

Why do we fall for sovereignism?

Much has been, little is left. After a tough election year, we will soon know the name of the next president. In the meantime, we offer an analysis of why sovereignism is taking root in contemporary Romania.

“The acting president of the Liberal National Party (PNL) has been appointed by the acting president of Romania as acting prime minister”. This was the headline on May 6th, the day after the results of the presidential elections’ 1st round were announced. And it is the perfect image of today’s Romania – an unstable and divisive one, since we started organising elections and practicing a type of provisional politics almost a year ago.

Distrust in the political class is the main reason why we are now in the situation of choosing between two candidates who tell us they are anti-system. This is also because those who promised us stability have given the people exactly the opposite through hand-picking candidates out of the race and canceling the presidential elections in the middle of it all, last November.

An IRES poll from last year shows that over 60% of young people do not trust state institutions and 90% believe politicians lie. Another survey, this time from INSCOP, shows that 66% of Romanians think Romania is going in the wrong direction and 68% say we are not all equal in front of the law. In other words, people are complaining about bad governance, corruption, clientelism and illicit enrichment – reasons enough for people to want a reset of the political class. There is a direct correlation between the level of satisfaction a citizen feels and his low trust in both the political parties and the system. A World Happiness report shows that the most virulent anti-system attitudes are found among the most dissatisfied citizens – they believe the parties have not done enough to protect them. An authoritarian leader does not scare them as they would be willing to give up certain civil liberties in exchange for a better living or a safer life, according to another survey. For Tiktok's patriot dancers, the sovereignism embraced in the elections means restoring dignity. "We kneel before no one" is a reaction after years of humiliation both at home and abroad, as Romanians are used to struggling to earn a living in an economic system with major inequalities and class differences. It is their response to an economic growth concentrated almost exclusively in big cities, while in small communities, people still lack the most basic necessities like roads, water and electricity.

The rise of extremist movements in Romania amid discontent with the political class is not unique in Europe. According to historian Tom Junes, it has its roots in the anti-communist movement and it’s a direct result of the way the transition from communism to democracy was characterized by inequality and the enrichment of the new post-communist elites. The opposition movements that started after the Revolution were not only about freedom from Soviet domination. They also came with patriotic rhetoric and an excessive use of the national flag. Anti-communist sentiments in the region fueled populism and made room for the far-right. And yesterday's anti-communist leaders have in time become today's extremists. We have seen this at Hungary's anti-communist activist and current President Viktor Orban, at politicians and authors Janusz Korwin-Mikke in Poland and Volen Siderov in Bulgaria, and locally, at Marian Munteanu (the leader of the students) and more importantly, at George Simion who, even though hasn’t participated at the 1989’s Revolution, has intensively promoted anti-communism in the following years.

But distrust in the system and social inequality are not enough for a right-wing populist movement to gain momentum. There also needs to be a major lack of trust between people, because where there is distrust, there is also a lot of polarization. The us versus them dichotomy has brought us to the point where family gatherings are a torment, the internet is flooded with hate, and fear is everywhere. What we may not realise now is that we have all fallen prey to treacherous manipulation.

Liviu Dragnea, the foremost cultivator of sovereignism throughout Romania, made a statement once that has stayed with me. In 2019, after the European socialists announced that they were freezing relations with the Social Democratic Party (PSD) because of their failure to obey the law, Liviu Dragnea claimed that there were, in fact, much bigger interests at stake because "it turned out, two years in a row we were the main producer of corn and sunflower in Europe". The information wasn't even entirely true, apart from the fact that I don't think anyone at the time imagined that Europeans were keeping their eyes off our corn and sunflower-filled plains. But over time, fed constantly by our politicians, the seeds of sovereignism sprouted in the minds and hearts of our fellow citizens. And so has the seed of hatred.

Let's not forget that the politicians who are now taking pro-Europe positions are the same ones who supported the so-called Coalition for Family, spread misinformation such as "the state wants to take away your children" and used homophobia as a political weapon without caring about the consequences within communities. "Romania needs to regain its national dignity, its national pride, its access to its own resources," said Liviu Dragnea a few years ago. This narrative, taken up by the Russian newspaper Sputnik and by the Chinese propaganda, I later heard recited by Călin Georgescu, this 'messiah' of our days, who is also strongly supported by the Russians.

The vote people gave on Sunday is a response to the superiority and disgust of how a sophisticated and open-minded Romania looks down to the rest of the country. The Romania that now tells the diaspora they are stupid, illiterate and should remain without their right to vote, but was grateful when their nationals living abroad voted for USR (Save Romania Union) in Parliament and elected Klaus Iohannis as president over Viorica Dăncilă. We are now witnessing the aftermath of years of politicians making a living off our money, delivering misinformation and Russian propaganda and lying to us that the shortages we see and feel have external causes related more with the EU. Meanwhile, we have been instigated by social media algorithms and emotionally manipulated by fake news and half-truths. Now we find ourselves face to face with them – the people that vote against the system, that are disappointed, angry, desperate and weighed down by the hardships of tomorrow, and whom we are trying to convince that our solution is, in fact, the one that could save us. The worst thing we can do now is to sharpen our knives against our fellow citizens. It is mandatory that we realize there are more similarities between us than we might at first glance.

Teodora Munteanu is a political scientist and journalist. She currently does journalistic research for content creators. She has collaborated with publications such as Pressone, Mediafax, Observator Cultural and Vice Romania.

Three books that give us different perspectives on freedom & inequality

Ruxandra Gîdei, the voice behind 4fără15 — the social media platforms bringing together over 100,000 readers, whom Ruxandra constantly invites to diversify their reading, shares with us three books she read and loved that talk about inequalities and freedom in Eastern Europe and beyond.

1. Free. Coming of Age at the End of History (Lea Ypi)

Albania's transition to capitalism mirrored that of Romania's in many ways – pyramid schemes, hasty privatizations that enriched the ‘new’ elites coming from old structures, the collapse of social safety nets, and deepening inequalities. True, after Hodja, the Albanian 90’s emerged as a much more violent decade, and our transition (albeit traumatic) was somewhat milder. But there are similarities.

An autobiographical tale, Free.Coming of Age at the End of History captures the deception of this transition, seen through the eyes of a young girl whom adults urge to completely abandon her convictions and embrace a new order. I would say it sheds light on the anger toward a system that, even 35 years on, has failed to offer equal opportunities to all.

2. Down and Out in England and Italy (Alberto Prunetti)

With his degree offering no job prospects at home, the protagonist tries his luck in the UK — only to find himself under Thatcher’s shadow, scrubbing toilets and serving food for abusive employers, always living in horrific conditions. It’s a book that challenges you to reconsider the hardships of migrants driven to political extremes, casting a critical eye on the neoliberal project as a whole. It’s also the funniest, most incisive and revealing novel about economic migration and precarity in a foreign country that I’ve read so far.

3. The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty (Daron Acemoğlu & James A. Robinson)

The third and final book on my list is an in-depth exploration of the historical and economic forces that have shaped various forms of government. Drawing on examples from ancient Greece, medieval tribal societies, interwar Germany, and contemporary societies, its central thesis is simple: freedom is rare and hard-won, only emerging in strong states that are still kept in check by a vigilant, active society. As we move away from this “narrow corridor” of freedom, polarization deepens. Though dense and complex, the book rewards your time and effort. In fact, it may even work as the perfect disconnect from the daily avalanche of news.

Vlad Nancă on representing Romania at this year’s Biennale of Architecture: “Our interest is to bring attention to how the human body is represented in 20th century architectural drawings and learn some lessons from that.”

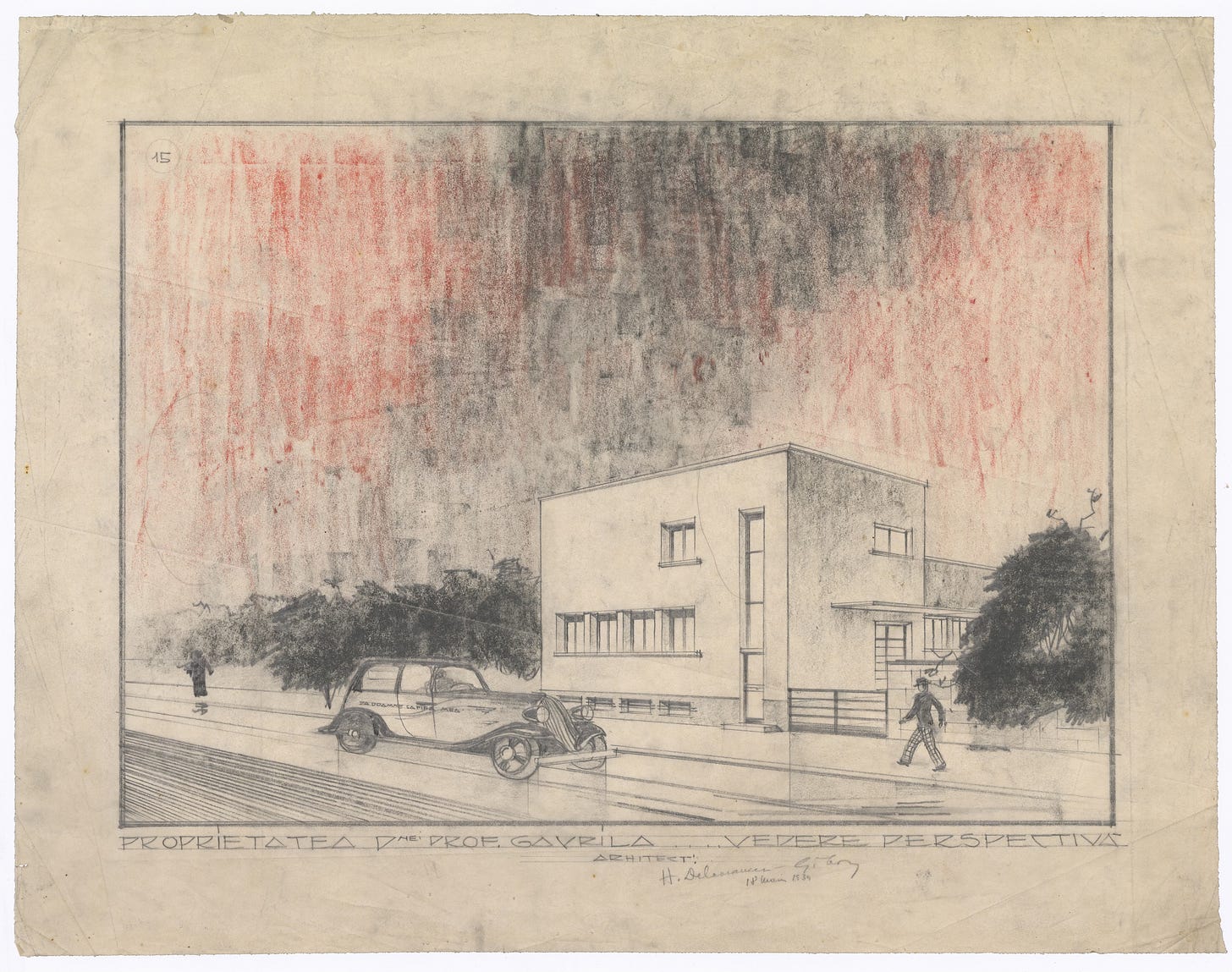

Yesterday was the launch of the Romanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of Architecture, where Vlad Nancă & Muromuro are representing Romania with Human Scale – an exhibition where visual art intertwines with architecture, highlighting the various forms of looking at and thinking of a space, through the use of arhitectural drawings made by some of the most prolific Romanian architects of the 20th century. Right before leaving to Venice, I sat down with Vlad over an espresso tonic (marvellous prepared by him) to discuss in depth his involvement in this year’s Biennale and how it all began.

Architectural drawing is at the heart of the Human Scale project, with which you are representing Romania at Venice’s Biennale of Architecture — an approach rarely seen. What is the meaning of Human Scale and how did it start?

Loosely translated, Human Scale is exactly what the title suggest: the human placed in architectural drawings to give scale to the proposed project. Our interest is to bring attention to how the human body is represented in 20th century architectural drawings and learn some lessons from that – like what kind of architecture was proposed in the 20th century – and to encourage people to think of human beings as the measure and main point of what we do and build onwards.

For me, attention to man does not mean that he should be the one who dominates other species, or nature. Rather that attention to human beings can also mean attention to a human inhabited space – including planet Earth, which I see it as an inhabited space – and how we reconcile these elements.

The project starts from a series of my own works that I started in 2017. Specifically, I focus on these scale-giving figures that are often drawn 1:100 or 1:200 in architectural drawing, and I scale them up to 1:1 and place them in my exhibitions as outlined sculptures. As I progressed with this kind of work, my interest in architecture grew, so I visited the architecture museum in Berlin and the architectural drawing collection in the UK, which made me want to have access to this kind of sketches in Romania, too. That's how the idea was born and the best occasion to start researching and looking for drawings was the Venice Biennale. And as soon as we started working on it, it became a joint project with the Muromuro Studio team (Ioana Chifu and Onar Stănescu) and curator Cosmina Goagea. Everyone's involvement made sense - from the conceptual level, where Cosmina contributed most, to the architectural design of the exhibition, realized by Muromuro. The final product is the result of everyone's research. There were many discussions between us and the drawings on display are works chosen by each one of us.

What have you discovered and learned during your research for the Biennale?

During research, we worked with drawings from the beginning of the 20th century. Sometimes aeven older – Ion Mincu’s, for example. The whole documentation process was a joy, I discovered and learned so much. I believe that accesibility to architectural drawing, could help people understand architecture differently, have new perspectives. That's what we're trying to do at the Architecture Bienale – most of the drawings we're exhibiting are being seen by the public for the first time.

I happen to be more passionate about architecture from the second half of the 20th century in Romania, but having greater access to drawings by architects like Alfred Popper or Ion Giurgea, I've discovered that I can also enjoy architects that I may have overlooked before. I see the city in a completely different light now. It's fascinating to discover drawings of buildings that I knew or vice versa – discovering buildings after seeing the drawings, but also how big an architect’s involvement was – they did absolutely everything, including the furniture. I think it is all the more important to open a museum of architecture, where there would be permanent access to sketches and drawings by architects – some of them absolutely fabulous ilustrators, like Tiberiu Niga, or Henrieta Delavrancea. These collections should be cherished and shown to the public.

Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to have access to drawings from the second half of the 20th century. They're either misplaced or in poor condition. Looking through the archives of the magazine Arhitectura and the student drawings from the ‘60s and ‘70s, we discovered that their works were fantastic! Those were the richest years in community building, like sports infrastructure, for example. There has been this ongoing discourse in the public space that everything that happened under communism was bad and people tend to overlook the value of the architecture of that time. I think we need to change our perception a bit.

As a visual artist, you've always been drawn to architecture. I’m curious where do you think it meets the visual arts and where do you feel they diverge?

Obviously, they meet in decorative and monumental art – both are passions of mine when it comes to my interest in architecture and the reason why I find constant inspiration in architecture. In the second half of the 20th century, in Romania, there were many monumental art projects. I'm referring here in particular to the mosaic works, some of them absolutely fabulous. Nicolae Porumbescu's interiors, for example, in Suceava or Baia Mare, where he also did the interiors. After working at Human Scale for the Biennale, an obvious observation is that architects tend to work for a beneficiary, while artists do not. I think this is where architecture and the visual arts part ways, the working methods are different.

Could you name a few buildings in Bucharest that inspire you and where could we find them?

Ion Giurgea's buildings – like the one at the intersection of Polona Street and Bd. Dacia (as you walk towards Grădina Icoanei, on the right side), or Tiberiu Niga's building on the corner of Calea Victoriei and Piața Amzei (where Velocita is located).

The Venice Biennale of Architecture will be opened until the 23rd of November.

Dumitru Gorzo on his work: “My best moments are when I'm working as if I'm not even there.”

One of the few contemporary Romanian artists who have exhibited their work outside of Romania, Dumitru Gorzo moves freely between forms – working as a sculptor, as well as a painter. He is known for works that are full of tension and his latest series, exhibited at Ars Monitor under the name Pictodrom is no different. With works painted in-situ on the gallery walls, as well as some previously painted in his studio in the US, Gorzo seems to be inviting the public for a dialogue about the world we live in today. Listening to him talk about his art at one of the talks organised by the gallery sparked my curiosity to get to know him better.

When you start painting, do you set out with an intention or a theme in mind? Or would you rather say you go with the flow and experiment?

The beginning of working at a painting always comes with a mixture of overlapping situations and states: the intention to do something, an idea that needs to be tested or just a red dot that you carry in your head and have to put somewhere. The process itself is one that resembles a form of chaos, things become clearer and settle down as you go along. My best moments are when I'm working as if I'm not even there.

I feel that with your new series – Pictodrom, you intend to describe how you perceive today's times – there's a lot of color, but also a lot of darkness, suffering. How would you describe – using your words this time, the context of today's world?

Complicated, intense, interesting. We forget that such times have been “normality” for most of known history. Do we like them? No! But that's another story entirely. Even if we plan it, or not, the state of the world we live in shines through, however piously, in our moods and actions.

What bothers you most and what helps you when you create?

What confuses me is somehow what also helps me sometimes. The state of discomfort given by the flight for form, for expressiveness, for a painting that means something, or more exactly something else. And then there’s insecurity, misunderstanding, distrust. But it's precisely these that get me out of the trap of ready-made solutions. I didn't make a method out of it and I don't go after unpleasant states, but I notice how most of the good things that happen in the painting I make come from places and states that are not really related to inner balance and harmony.

You said at the opening of the Pictodrom exhibition that for you, painting on a white canvas is an act of violence against it – something that have stayed with me ever since. Could you tell me about the origin of your need to paint? Where does it come from and what does it bring you?

The ongoing construction of the self. A way of justifying my existence – which in itself is wrong, given that existence is already justified by... existence. A clean surface, whether a canvas or a white sheet, is somehow perfect. You could do nothing to it. So the beginning of the work on that white surface comes as an external action, an attack, and requires a few other interventions to get to a point where the painting seems satisfactorily. More often than not, it's not enough, and it requires another act of violence on the work, which sometimes isn't enough either.

You chatted to a lot of people who came to the opening - did anyone's perception of your paintings in particular surprised you?

At openings, and not only in Romania, people usually come to see and find out more about the paintings. Launches of this kind are not seen as places where the public can be active. And that's a shame. I still dream of events where people discuss and argue. Where visitors allow themselves the vulnerability that comes with exposing a personal opinion or observation.

Pictodrom is opened until the 29th of May at Ars Monitor.

EDITOR’s PICKS

As always, this newsletter ends with the editor’s picks and because I’ve been travelling to Morocco recently, for a two weeks trip with my mom, this month I’ll be sharing the best places I discovered in this marvellous and surprising country.

Morocco has gave me back my faith in humanity, which no other trip did and helped me change my perspective regarding muslims. A country so diverse in landscapes, with the kindest people and some of the most beautiful handmade objects I’ve ever seen, Morocco should be definitely on your list and you can start by adding the places below.

A lovely place we stayed in was L’ma Lodge, in Skoura. In a city that’s on nobody list and is seen more a stop on your way to or from the desert, L’ma really makes you think twice if you should just pass by or spend a few days more in this paradise. With a lush big garden, a pool, a petanque court and lots of places to relax, L’ma Lodge offers amazing food and spa services. Owned by a belgian woman and her french architect husband, it seems that anywhere you look, you see something beautiful and inspiring. I would go back anytime!

A shop we spend too many hours in was Lahandira, the rug store in Marrakech. Owned by a Moroccan family, this place is a gem if you’re looking to buy authentic new or vintage berber rugs. With prices going up to a few thousand euros on the antique ones, there’s something for anyone and you’ll sure won’t leave empty-handed.

A city that impressed me was Rabat, the capital of Morocco. As all Moroccan towns, it is divided between the old part — the medina, and the new neighbourhoods. While the medina is similar to others we’ve seen across the country, the new part of the town is so green and chic. With green spaces on cliffs overlooking the ocean, to classy neighbourhoods of houses, Rabat is a city that needs at least 2 days to be discovered!

A restaurant we went to and enjoyed was Le Petit Cornichon in Marrakech. Situated in the modern neighbourhood of Guéliz, this lovely boutique restaurant mixes the idea of bistro with the exquisite tastes of a fine dining restaurant. The food is delicious and the place has one of the biggest wine selection of Morocco.

What we enjoyed and recommend the most in Morocco is taking a cooking class with a local family (a MUST if you want to get to know the locals better), staying in riads rather than hotels and visit at least one big souk (either in Marrakech or Fes) for the amazing handmade objects they do, from tannery to wood, ceramics or brass.

A bientôt!